During a tempestuous first half of 2016, global equity markets had modest but positive performance while bonds were the big surprise by outperforming stocks for the period:

- The broad US stock market rose 3.8%.

- Global stocks gained 1.4%.

- Investment grade bonds returned 5.3%.

- Value strategies beat growth by 5.5% to 1.4%.

- Small cap stocks beat large cap stocks by 5% to 3.8%.

- Developed non-US stocks had an aggregate loss of 4.4%.

- Emerging market stocks outperformed developed markets with gains of 5.8%.

- Inflation remained subdued at 0.9%.

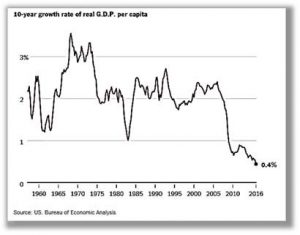

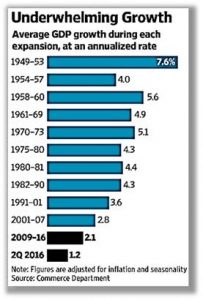

The economic backdrop during the first half of 2016 was positive but not overly so. Traditional unemployment measures seemed good, near 5%, but the economy only grew at an inflation adjusted annual rate of 1% for the period. That makes for an annual average GDP rate of 2.1% growth since the end of the recession in 2009, the weakest pace of any recession recovery since 1949.

Had the American economy performed as the Congressional Budget Office forecasted in August 2009— consistent with historic trend—US GDP today would be about $1.3 trillion, or about 7%, higher than it is. The year 2016 started with the worst opening week ever for U.S. stocks, off about 6% for the first five trading days of the New Year. But during the balance of the period, stocks were able to struggle back to show positive returns.

Fixed income traders were surprised by the turnaround in the bond market. In January, Goldman Sachs and Pimco, dominant players in the bond market, predicted benchmark US 10-year yields, then 2.2%, would climb to 3 percent by the end of 2016. On June 30, the US 10-year yield had declined to 1.5%. And most economists expected the Fed would raise its benchmark federal-funds rate at the March policy meeting and at least one more time this year; yet, the Fed did not raise its rate at any time through July 2016.

At mid-year with the S&P500 over 2000 and reaching historic highs in July, the US stock market seems far overvalued by historic metrics. Although the overvaluation of the stock market is well short of the extremes reached at the year ends of 1929 and 1999, it is at or above the other previous peaks of 1905, 1936 and 1968.

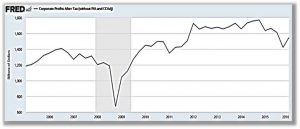

S&P500 earnings per share continue to fall in what is one of the worst declines in decades. Yet corporate profits are still very high by traditional measures and profit margins are near all-time highs. Corporate profits, both as a percentage of GDP and relative to labor income, remain at or near record levels.

The year 2016 has been filled with unexpected and too often unwelcome economic news:

- The International Monetary Fund cut its outlook for the world economy, warning that economic turmoil in China and financial contagion throughout emerging markets threaten to curb global growth.

- Japan’s central bank stunned the markets in January by setting the country’s first negative interest rates, in a further attempt to keep the economy from sliding back into the stagnation that has dogged it for much of the last two decades. The Bank of Japan is now the second major central bank to set negative interest rates, joining the European Central Bank, which first did so in 2014. The central banks of Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland also have negative interest-rate policies. Then in March, Japan sold for the first time new 10-year bonds with yields below zero.

- The United Kingdom voted to leave the European Community (“Brexit”) in June. The vote was immediately followed by the deepest global stock market drop since 2007, as investors dumped risky assets and rushed into safe havens. And yet, as of July 1 most of the post-Brexit equities sell-off had been erased.

- In early July, the interest rates on 10 and 30-year US Treasury bonds reached all-time lows of 1.3% and 2.1%, respectively. Record-low 10-year interest rates were also registered in Germany, France, Switzerland and Australia. Notably, Swiss 50-year interest rates are now for the first time negative.

- Rates are negative in Germany up to 15 years; and in France up to nine years.

Stuck in a New Mediocre?

Given current economic and market conditions, investment returns are expected to continue to be more volatile and lower than historic averages. Both stocks and bonds are already very highly priced, driven there in large measure by the massive monetary expansion that the Fed and other Central Banks employed to fight the financial crisis and its aftermath.

Are markets and economies stuck in a “new mediocre” or a “secular stagnation”? What options are there for public policy?

Traditionally, the key macroeconomic policy levers available have been two – monetary easing and increased public spending.

But the already heroic monetary policy efforts by Central Banks globally have not yet been sufficiently successful, and with interest rates in negative territory in many parts of the world, it is clear that using monetary policy to stimulate the economy has limits.

And yet, turning to fiscal policy, the US Congressional Budget Office in February delivered the bad news that the national debt is now rising faster than GDP and heading toward unsustainability. The national debt hit $19 trillion for the first time in 2016 and the US debt-to-GDP ratio doubled in the past decade. This leaves little political room for traditional fiscal spending initiatives that rely on debt funding. That said, many macroeconomists think it is time for a ramp-up of public spending that is sufficient to move the economy much closer to full employment and output.

Absent such a fiscal boost, or possibly a surprise inflation spurt, this current macroeconomic adjustment period that feels so mediocre will likely continue a lot longer. An unexpected rise in inflation could be a catalyst to both growth and the easing of the debt burden; such an inflation surprise could result from coordinated fiscal and monetary policy.

It is instructive to look to Japan today to see how these processes are working where there are similar

problems. In July, Japan’s Prime Minister Abe announced a $265 billion fiscal stimulus. He is seen to be pressuring the Bank of Japan to coordinate with the government by stepping up monetary stimulus. That created speculation that Japan will resort to “helicopter money.” Milton Friedman, the Noble Prize winning economist who coined the term “helicopter money,” believed that Central Banks could halt deflation or increase inflation by distributing money directly to the population, by even dropping currency by helicopter if necessary as he described it once. Former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke drew attention to this possibility when he visited Tokyo in July. The markets sensed that Mr. Bernanke was called on to bless helicopter money. Mr.Bernanke and others have refined the definition to include fiscal stimulus alongside a permanent increase in the money supply.

It is also instructive to note the current discussion about whether the US’s borrowing capacity has gone up as interest rates have plummeted; it may come to dominate earlier concerns about the national debt. With the US Presidential election candidates responding to the high level of economic dissatisfaction with promises to get the economy moving again, it would not be surprising to see whomever is in the White House next January to pursue vigorous fiscal expansion, and possibly in coordination with the Fed.

All told, this economic landscape suggests that investors should continue to expect more modest returns than usual and remain defensively positioned. To this end, we recommend that investment portfolios lower normal allocations to stocks, emphasize high quality securities (both stocks and bonds), and include meaningful inflation hedges.